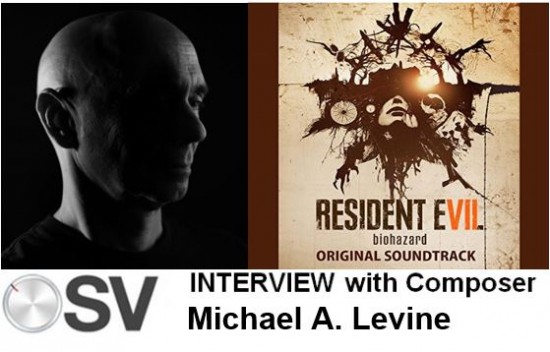

What is Brave Wave’s Street Fighter II The Definitive Soundtrack? It isn’t a remix album and it isn’t necessarily a new arrangement of the music, although you could easily be convinced otherwise. It’s the first in the label’s Generation Series that aims to painstakingly revitalize some of gaming’s unreleased, incomplete, or poorly preserved soundtracks. For Street Fighter II that meant making new source recordings directly from Capcom’s CPS-1 (Street Fighter II) and CPS-2 (Super Street Fighter II Turbo) arcade hardware.

A lot of work went into cleaning up the recording before it was finally mixed and mastered and ultimately signed off on by original composer, Yoko Shimomura. Did the months of delicate, elaborate work pay off? Play the side-by-side comparison within and know that you’ve never heard Street Fighter II’s music so clearly before, and not just because you aren’t in a raucous arcade.

Fighting games and I are fair-weather friends at best. I’m not competitive or determined enough to master any character but even I couldn’t resist the original Street Fighter II’s hype in the arcade. It’s still my favorite entry in the series — one I’ve loved listening to for nearly 25 years — but this compilation made me realize that I’ve barely heard any of it. Sure, I know the main character themes by heart but I’ve never beaten the game with each character, never spent much time with Super Street Fighter II Turbo and I totally forgot there were “critical” versions of all the themes. I was just hoping for a cleaned up recording of Zangief’s music but I got so, SO much more.

The album encompasses a whopping 115 tracks with 46 representing the original Street Fighter II, 68 from Super Street Fighter II Turbo and a final track of voice and sound effects. The physical releases span four gorgeous blue and orange vinyl LPs or three color printed CDs. I don’t own a turntable so I was spared the heartbreak of seeing the vinyl editions sell out instantaneously. I opted for the CD version which comes in a standard double-disc jewel case with that classic album art and Brave Wave’s simple but stylish packaging. Inside are the three full-color discs adorned with Ryu, Bison and Dhalsim artwork and simple labels denoting CPS-1 (Disc 1) and CPS-2 (Discs 2 and 3).

The liner notes start with an introduction from Brave Wave and a huge tracklist page followed by a foreword from Capcom’s Yoshinori Ono. The current Executive Producer of the Street Fighter series, Ono relates his experience with the games, its music and Shimomura’s influence with his trademark boyish charm. Most interesting are the following pages with a short Q&A from Yoko Shimomura. It’s not a pensive tell-all interview but she does briefly explain how Super Mario Bros. and Dragon Quest inspired her and how she lucked into working on Street Fighter II. Best of all, she adds a few thoughts on each character’s theme and what she had in mind while composing them. Finally, Matt Leone from Polygon.com relates his own unique experience with the series after spending most of 2013 absorbed by a Street Fighter retrospective piece. Interspersed are more (but never enough!) vintage Capcom illustrations from artists including Akiman and Kinu Nishimura.

Street Fighter II: The World Warriors (1991, CPS-1)

The music itself is even more lovingly produced than the physical trimmings. At first it just sounds cleaner than I remembered but as Ryu’s theme begins there’s a new depth to be heard in the syncopated pop of the traditional Japanese percussion. The drums and claps start Zangief’s theme with a bang and the warbly, tinny main melody sing over a newly restored bass line. Blanka’s theme in particular sounds like an entirely new song. The drums, the organs and the layers of melody come at you fast and unyielding. It’s a totally new vibe that fills the space this restoration has swept clean, and it happens with nearly every track.

Then there are the eleven ending themes; surprisingly upbeat vignettes evoking Ryu’s hunt for the next challenge, Ken’s unexpected reunion and Chun-Li’s graveside prayer/female awakening. I’ve never seen all the endings in the game but from an audio standpoint they serve as unique accompaniment to each of the characters’ themes. Similarly, the next twelve “Critical” tracks take the character themes and tweak them up to lightning speed, played when their health dips dangerously low. The endings and criticals are nice to have for the sake of a definitive collection but they aren’t as repeatedly listenable as the main themes.

There are also the remaining jingles for “Continue”, “Game Over”, “Victory”, “Ranking”, “New Challenger” and even a rare “Unused Jingle” that Brave Wave dug out of the game. It’s all capped by the Staff Roll which soars high and triumphant with a fast paced melody and driving bassline. It has that perfect feel that puts a bow around the entire Street Fighter II experience no matter how you played or listened to it.

Super Street Fighter II Turbo (1993, CPS-2)

After two years of hardware advancements the CPS-2 brings more layers, fuller bass and an overall smoother sound that remains a major point of contention for Street Fighter music fans. The sound is definitely clearer and more nuanced but for me it lacks the personality of the original; it really depends on which version you encountered first. The structure of the music hasn’t changed much between the two versions but the instrumentation clearly has.

Nevertheless, Super Street Fighter II Turbo gets the same loving restoration as the original along with the addition of five new character themes. It’s presented in the same fashion with a playlist of 67 tracks for main themes, endings, criticals, all the jingles and another “Unused Theme” found hidden in the hardware. Don’t fear, fans of Super Street Fighter II Turbo, my brevity with this larger part of the compilation doesn’t mean it’s lacking or unimpressive. The production and scope is as definitive as the Street Fighter II portion.

From the packaging to the playlist and the audio itself, Street Fighter II The Definitive Soundtrack is exactly that: definitive. At the same time it’s also symptomatic of a greater problem facing video game preservation. Until Brave Wave did all this work we had no idea how much fidelity was lost in our previous OSTs, mp3s and gamerips. It’s worth buying the album just to support future conservation efforts like this. If preservation isn’t a concern of yours you can still regard this album as the definitive collection of Street Fighter II music and one well worth buying digitally or physically.

Tags: Brave Wave, Capcom, Music Reviews, Reviews, Street Fighter II, The Generation Series, Yoko Shimomura

I am also concerned with video game and game music preservation, but, in terms of presenting the music exactly as it is in the games, this album falls quite short. There’s a FACT Magazine interview where the Brave Wave team talk about how they have manipulated and “modernized” the sound of the music, particularly the CPS-2 tracks.

http://www.factmag.com/2015/12/03/street-fighter-ii-soundtrack-interview-brave-wave/

In addition to the heavy use of equalization, the volume of all tracks has been boosted significantly, very frequently into clipping. It’s ridiculous to me that clipping happens at all, given how easily preventable a problem it is. Then, almost comically, the volume was lowered by just under 1 dB for almost all tracks (The CPS-1 “Blanka’s Theme” is the only exception for some reason), after the damage was done. While I haven’t heard any audible distortion caused by this, it is indeed present and it seems wrong to me to describe any album’s sound as definitive as far as preservation goes when it introduces this unnecessary and avoidable distortion not originally present in the music. It’s a pedantic complaint, but perfect preservation calls for minute attention to detail, even inaudible ones.

I don’t mean to sound grouchy or pessimistic in saying this, but after this, I have little faith Brave Wave will pursue faithful representations of any further game’s soundtrack they release. Not that they won’t be worth owning or listening to or even the best versions musically speaking, they just very likely won’t be accurate documents. That’s something noble to pursue, it’s just not the same as preservation and shouldn’t pretend to be.

Thank you for the well stated reply on what you must think is a not-so-accurate review. I admit, my new found excitement over preservation seeped in at the end there. I didn’t mean to make this sound like it was the authentic, 100% original arcade music, it clearly isn’t. I didn’t examine the waveforms or anything to see the near-clipping you mentioned but to me personally the sound is vastly expanded over what my ears remember. Of course, like how we remember games looking better than they actually are, my memories are probably just as fuzzy.

Are you involved in any preservation projects or efforts? I really want to get involved in some capacity, be it helping to archive the untouched sound files directly from a disc or even preserving marketing materials that revolve around games. Scans of old magazines and artwork is what I’ve done the most of but so far it’s just been a hobby really.

Don’t get me wrong, I don’t really have any problem with your review! I just wanted to point out the shortcomings of the album as a preservationist document, which I was disappointed to discover because naming it “The Definitive Edition” gave me the impression that it was intended to be one.

I’m not really involved in preservationist efforts. To archive sound files from the discs and especially ROMs often takes programming/hacking skills that I don’t have. I don’t know if you’re acquainted with the game emulation scene, but for many of its contributors accuracy is of the highest importance because of their preservationist philosophy. I’ve run a few hardware tests and advised on how to get more accurate sound for a couple emulators, but I am incapable of making the changes myself. At the moment, I’m especially interested in Nintendo 64 sound because emulation of it is so imperfect.

I’d love to make archival recordings myself, but I think I need to upgrade my gear to the point that its noise and any other characteristics are effectively removed from the recordings and the result is just the pure output of the systems. But then I also wonder, what does definitive and archiving really mean? Take the Sega Genesis as a demonstration. There are three models of the console which are each significantly different, including in sound, and then within those models there are revisions that also sometimes are audibly different from others. How do we approach archiving Genesis soundtracks? Record from each version that produces significantly different results from others? The Genesis produced sound using an FM synthesis chip and a separate PSG chip (the same one used in the Sega Master System) and mixed the two together in the analog domain, producing variations in volume level between different individual consoles. How does one address that for archiving? The first model had mono RCA and stereo headphone output; should both be archived? There are also mods that can be done to the circuitry to clean up the signal, with optional removal of the treble filtering all Genesis models do. That would be a truer representation of the sound chips themselves and therefore the music, and can produce better subjective sound quality, but it’s not really the true sound of the Genesis, so what should be done? Should both be archived? So does that mean, for completeness’s sake, all soundtracks should be recorded from each significantly different Genesis revision from multiple individual consoles for each, in both mono and stereo when applicable, stock and modded, with treble filtering and without filtering? That would be a massive undertaking, but the differences for each recording wouldn’t be just academic. The sounds are different enough for most of the variables I mentioned to be noticeable to the average attentive listener upon fairly casual comparison. And if these things aren’t archived, once the last system of any of the many revisions stops working, its unique sound will be lost to history. Emulation of the digital components can be perfect, and the analog components can be approximated to functional perfection as well, but there tends to be a distinct lack of emphasis on the analog parts of these systems in emulation. I don’t want to sound overly dramatic or to wax poetic, but I hope these sounds, which are the result of many people’s hard work, are a part of many people’s fond memories, and are simply historical facts that I think are worth documenting due to their sheer existence, won’t get lost.

The one effort I’d seen that I thought was pretty smart for pure archiving was to backup the sound files on disc-based games. Not recording the music but preserving the files that contain them. That saves it from bit rot of the disc but then it’s the same problem you mention with the Genesis. Several versions of the PlayStation exist and emulation would have to faithfully recreate the sound hardware and the software the game used to unpack it or play it back.

The Genesis talk reminds me of my own funny predicament. With the original Sega CD you could use the volume slider on the Genesis to mix some parts of the game music. That slider is something I don’t remember any emulator pulling off and there are some songs I’d really love to play around with and record.

For real, though, your questions are what is so frustrating about game preservation. The interplay between software and hardware is unlike any other media format and it’s going to take a while before people figure out a good way to preserve both in as authentic a way as possible.

The games themselves are being preserved, no problem. The CD ones with Redbook audio take a little effort to ensure no errors since CD audio has no in-built error correction like other digital media do, but it’s still getting done by people. With a little cracking, the recorded music streams found on games can be decoded and played back on a computer, and that’s the purest way to hear it. But again, it’s like modding the Genesis to get the sound more directly from its chips; it’s better quality but it’s not the real sound of the system because of the processing or various degradations that can arise in the signal path from whatever handles audio on the system up to and including its output.

But of greater concern preservation-wise to me are the games whose music is synthesized by the console hardware. Firstly, playing the music data from those games on a computer requires emulation, which can produce the exact same results as the original hardware but almost never does at present because of how difficult it is to do, especially without official documentation as to how the hardware functions. But also, ideally I’d want to capture everything output by the system, including inaudible infrasonic frequencies, just for the sake of truly preserving /everything/ for posterity and things like research and analysis purposes. Funnily enough, even though they’re relatively simplistic in terms of the technology and sound produced, it’s actually harder, indeed impossible using even modern professional equipment, to capture the full audio output of old systems like the NES or Game Boy because of the extreme frequency range they produced.

I’m gonna get technical here on the off-chance there’s another audio/video game nerd out there who would love to read this. This is likely to go beyond nearly everyone’s interest level, but I’ll try to keep it as comprehensible as possible.

In the most basic terms, in digital audio the maximum sound frequency that can be recorded (or produced) is half the number of samples of the sound wave recorded (or produced). CDs use a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz, so the highest pitch they can contain is 22.05 kHz. The NES sound chip’s sampling rate is 1,789,772 Hz. That means the highest sound frequency it produces is 894,886 Hz. Given the nature of the waves it produces, it does in fact create sound all the way up there. The maximum PCM sampling rate of commercially available professional recording equipment is 384 kHz, making it incapable of getting even close to capturing all of that. There is a filter that should cause the sound to decrease to nothing before that nigh-900 kHz point, but I know for a fact that my unmodded NES’s sound is going strong all the way to the top of my 192 kHz recordings of it, and it can be modded to get stereo sound and remove any filtering. It’s so high I have no way of measuring at what point it actually stops.

Audiophiles out there may be familiar with the supposed alternative to PCM, DSD, which records at over 2 MHz but with only 1 bit per sample. The bit depth determines the maximum difference between the loudest and quietest possible sounds that can be recorded. CDs have 16 bits per sample, enabling them to have a difference of over 90 dB between the loudest and quietest sounds. At the lowest levels of this range is going to be noise, but it’s possible to concentrate this noise in the less-audible higher frequencies. DSD’s 1-bit nature causes it to have an inherently huge amount of noise which then gets pushed up to just above a CD’s frequency bandwidth where it then rapidly reaches extreme levels, making it even less suitable. Increasing the sampling rate even to DSD’s highest of 11+ MHz still won’t do it.

The technology does exist to capture all this sound. Analog-to-digital converters, even ones that aren’t so-called high resolution, typically record a bitstream that is 2, 4, or more bits – which drastically cuts down on the amount of noise – with a sampling rate in the multiple MHz, but they then cut this extra data down to the desired format. Making anything more than a basic cut or paste in editing produces extra noise down at the bottom of the volume range 1-bit, but at CD quality this is generally inaudible since the bottom is way down there. But the bottom in 1-bit recordings is only 6 dB below the top, so DSD recordings are imported into software for editing that adds bits so that huge level of noise inherent in 1-bit systems doesn’t multiply in editing. However, as far as I can find through searching, there are no devices made at any price range that record directly to this multi-bit, ultra-high sampling rate format without downward conversion, which I believe would be the only method to record the total frequency range generated by an NES without also polluting it with noise.

All of this is literally totally irrelevant for the purposes of listening to music, since abut 880 of those kHz are inaudible to humans and can’t be reproduced by speakers anyway, haha. Just thought I’d point out the craziness it would take to truly archive everything on these old systems.

While I’m not totally keeping up it is fascinating to think about all the sound space that is and isn’t captured, by recordings and conversion and even our own ears. I’m with you though, even what we can’t hear should be preserved if at all possible.