One of the most heated subjects of debate among the writers here at Original Sound Version is whether or not it is essential for one to experience a soundtrack in its original context in order to properly review, enjoy, appreciate, or analyze it critically.

As musicians, music lovers, writers, and music critics, it is imperative that we give this music the opportunity to speak the way the composer intended. With amazingly few exceptions, scores are written for their subjects after – at the very least – the basic concept is fleshed out. In the case of film, most of the time, the movie has finished being edited before the composer lends his hand. If this is the genesis of scores, it must be accepted that these composers are writing this particular piece and this particular score based on something. It is safe to assume that without this inspiration as the impetus to the score, the work would not have been written – at least, it would not have been written the way it was (There have been instances where a piece was originally written for another project and then wonderfully added to the current work [i.e. “Regurgitation Pumping Station,” “Rain Rain Windy Windy,” and “Jelly” from Kyle Gabler’s World of Goo soundtrack], but this is less common).

How, then, can we possibly ignore the very basis of these scores? By definition, they are designed to accompany, enrich, and flesh out the drama in the games and films we love. Listening to an original score for a game without seeing/playing it is like ignoring the lyrics to a song.

Editor-In-Chief, Mr. Jayson Napolitano, has a valid retort (though he is of equal mind for both camps) in that publishers will often sell the soundtrack as a standalone product so should therefore be able to stand on their own merits individual of the games/films they score. Anyone who reads this site is familiar enough with soundtracks to know that some exist on their own better than others. A score like that of Bear McCreary’s Dark Void or – most recently – Petri Alenko’s Alan Wake are two examples of great works that can live heartily outside of the realm of their subjects – there is no denying this. Even still, both of these scores work far better in their respective games. However, scores like Bioshock 2, Red Dead Redemption, and the recently released (and terribly underrated gem) Singularity do not stand as tall out of context, but it I would never dare to say or believe that this diminishes their musical integrity, dramatic necessity, or listening enjoyment. Once these moments have been experienced by the listener, the music does work and is, therefore, a viable product – certainly as viable as any “compendium” or “manual” on a show or movie. Why should a score be viewed any different?

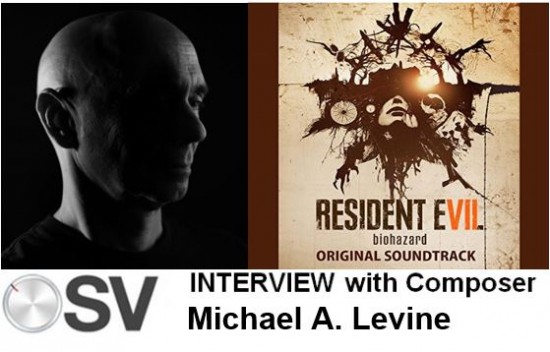

But, who am I to suggest how a composer would prefer his music be experienced? Why not ask the composers themselves? Well, that’s exactly what I did. First on the docket was the great Garry Schyman, composer of Bioshock, Dante’s Inferno, and Square Enix’s upcoming Front Mission Evolved.

The question I presented read as follows:

1) If given the choice, would you prefer your soundtracks be first experienced in context (either watching your film/game, or playing said game), or as a stand-alone (listening at home on stereo, “out of context”, etc.)? Naturally, we are assuming the audio quality is equally fantastic.

2) Why?

“I suppose if I had to answer it would be to hear it in context of the game and then to hear it on it’s own as music,” replied Schyman. “Not sure I have a logical reason other than intuitively that seems like the proper order to fully understand what and why I have written the music I have written.”

Couldn’t have said it better myself!

I wanted another perspective for the sake of discussion and I found it. I asked Red Faction Guerrilla and Command and Conquer 3 composer Timothy Wynn what his take on the subject was.

“Ideally I would like my soundtracks to be experienced on their own, outside of the game. Often times with sound efx [sic] and dialogue the music can get lost in the shuffle. I always try to create music that is interesting on its own right. If it doesn’t sound good outside the game, there’s a good chance it won’t be effective during the game. That being said, I think it can be interesting to play the game after hearing and getting familiar with the soundtrack. During game play, there can be many edits to the music cues. More often than not, cues aren’t played linearly. When I first play the final version of the game, I get thrown off because I anticipate the pacing and structure of the music cue I wrote. Sometimes the music changes in a good ways, other times not. It really depends on the pacing you are playing at.”

Perhaps it is telling that several months before this answer, I complained to Wynn that his fantastic Red Faction score was not as audible during gameplay cinematics as I wanted it to be. Serves me right! As for Wynn’s response, he is a seasoned veteran who has done several scores so I suppose I can’t chalk it up to one or two underwhelming sound designers or engineers.

Wynn has a fair point in that there are times where the music’s full potential isn’t realized in games thanks to the crazy action or other sounds on the screen. The number of games that do it right (certainly of late), however, far outweigh those that are less successful in marrying the score to the action. Recently, Darksiders found the balance perfectly; a great score was beautifully interwoven into a game that, by itself, may not have been the most pioneering or interesting, but using the story and score created a masterpiece.

"All those who wage war listen to music in its proper context." - Actual quote from game (not really)

Last but not least is the newcomer Joshua Mosley who sploded our minds with ‘Splosion Man last summer on the XBOX Summer of Arcade.

His answer was most direct:

“1) In Context

2) I personally have always liked to enjoy other composers music in the context of the gaming experience or film first. I like to see how it enhances the game/film experience. Listening to the the music in context makes it feel a little more “alive” in that sense. Like another character in the film/game, drawing out different emotions.”

Mosley’s answer is the one that best articulates my feelings about this debate. Interestingly enough, Mosley used his experiences of other composers to color how he feels about people listening to his own.

Just ask yourself, what would the theme to Super Mario Bros. be without the thoughts of hopping around and shooting fireballs? Would it really have the same meaning? Would you care about it all? Does not your heart soar and skin tingle at the end of the original Star Wars when we hear that gorgeous Force theme alongside Alec Guinness’ “Use the Force, Luke!”? Would it still be gorgeous without that context? Of course. It’s a great theme. Does the context take the score to new heights? You betcha.

I am not implying that a score cannot or should not be enjoyed out of context. I am simply saying that I feel listening to it in its original context will more often provide the listener with a more “enriched” sense of the piece and – ultimately – a better experience. Having said that, I can no sooner tell someone how to enjoy his music than I can tell him how to cook his own steak. But, if one wants to be a true connoisseur of music and music criticism, and if one wants to experience the score as [most] composers intend, he should always keep in mind that context is everything.

Tags: 'Splosion Man, Bioshock, Editorials, Features, Garry Schyman, Joshua Mosley, Red Faction Guerrilla, Timothy Wynn

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Zen Albatross, OSV. OSV said: Editorial: Context Is Everything http://tinyurl.com/2evmxz3 […]

I love this article, and I love this discussion. I think the headline is a little … zealous. Certainly context isn’t *everything* … if it were, I’d have no reason to listen to, or enjoy, soundtracks for games I’ve never played. But context isn’t *nothing* either. The question is a matter of dominance, I suppose. Post-modern power-struggle junk and all that. We were trained to think this way in college, right?

Great work talking to composers and arguing your case.

Yeah, great article, Gideon. It’s really a tough debate. As Patrick mentions, we all enjoy scores for games we’ve never played. There are soundtracks that have inspired me to go play games that I skipped, and soundtracks that I don’t care for out of context that I learn to love after playing the game (Chrono Cross and Demon’s Souls, looking at you!).

Then we get back to that thing with companies selling it as a standalone product. I don’t remember who I was talking to, but I remember a composer telling me he wished all games came with the soundtrack packed in. You’re buying the game, and should therefore have free access to the music contained within. That’s a happy medium in that you’re likely not buying the game for the soundtrack, and will have the soundtrack disc handy in the event that you liked what you heard while playing the game. Interesting idea!

Also, great pictures!

I think it’s a reasonable debate, if you want to call it that. However, this is a soundtrack review site, not a game review site. Listening to the music on its own merits is inevitable.

While I sometimes find a game itself enhances the experience of the music that was written for it, mostly due to nostalgia, it’s definitely no prerequisite. Many of my favorite soundtracks are from games I’ve never even played. In fact, there are cases where I will listen to a great soundtrack, and then try out the game, only to be disappointed with how it was used or the game as a whole (e.g. Unlimited SaGa).

I also feel the proclamation about game music being specifically written for the game is a bit of a generalization, since not all composers work with the same level of contour to the subject.

Though keep in mind I also don’t pay attention to the lyrics in most of the songs I listen to (which have them [and that are in English]).

[…] Original Sound Version debates this issue: “One of the most heated subjects of debate among the writers here at Original Sound Version is whether or not it is essential for one to experience a soundtrack in its original context in order to properly review, enjoy, appreciate, or analyze it critically.” […]