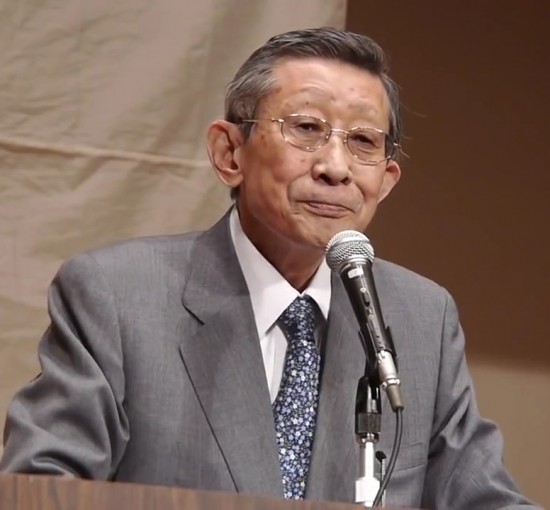

Koichi Sugiyama may not be a familiar name to a lot of gamers in the West, but he is a very well known figure in Japan. He is the man behind the music of the Dragon Quest series (originally released as Dragon Warrior in the West), which despite having only achieved an overall modest success in the United States, is very popular in Japan. Koichi Sugiyama’s style for the music that he writes for the Dragon Quest games is very unique, and it has been a significant influence on other video game music composers as well. I’ll be going through some of his work on the primary games of the Dragon Quest series and taking a look at what makes his music uniquely his, and how his style has changed over the course of the series.

For starters, one thing that sets Koichi Sugiyama apart from a lot of other video game music composers is his background. While many video game music composers are relatively young (or were relatively young during the early era of video games), Koichi Sugiyama actually began to write for the Dragon Quest when he was already in his mid-fifties. He already had a long musical career behind him, including music for films, TV, and Anime series. He has experience not only as a composer, but as a conductor and orchestrator as well. This led to him being involved in numerous live concerts of the music of the Dragon Quest series, among the first life concerts of video game music to be held in the early era of video games. He frequently conducts the concerts, and writes all of the orchestrations. This is a key part of his style, and these orchestrations have later been the basis for re-arranged versions of soundtracks used in remakes of the Dragon Quest series.

So, Sugiyama is very experienced in the orchestral setting, and this plays a very big role in his musical style for his video game music compositions. When he’s not limited to simple NES wave sounds, orchestral textures are definitely his favored choice; he rarely uses rock or pop instruments, techniques, and textures. His style draws very heavily from different eras of the classical repertoire, especially in his earlier works. And when he orchestrates his works, those orchestrations can sometimes make a very large difference in the feel and sound of the track. However, as time goes on his style does gradually become less heavily classically influenced. While it still remains very orchestral, he starts to incorporate more typical “video game” elements, such stronger emphasis on melody, more chordal harmonies and stronger dissonances.

In the very first Dragon Quest game, Koichi Sugiyama established a very basic formula on which he has elaborated and expanded in all of the subsequent games. The first game has 8 pieces of music: The overture, the castle music, the town music, the field music, the dungeon music, the battle music, the boss music, and the ending theme. It’s pretty straightforward, and while he has added to it, each game contains these core pieces of music, and they share a lot of similarities. I won’t cover examples of every piece of music, but I will go through a few to point out some different elements of his style.

Let’s start by taking a look at what is almost certainly the most iconic piece of music he’s written for the series: the main overture.

This track opens every single game of the series, and although the introduction changed beginning with Dragon Quest IV, the core part of the track remains the same. It draws a lot of inspiration from the Romantic classical period, particularly opera. The melody itself definitely has some aspects that come across as cheesy, and the orchestration is fairly muddy compared to some other examples from the series, but it works very well for it’s intended goal; a grand overture to introduce a medieval-fantasy adventure.

Koichi Sugiyama’s castle music is probably where his classical influence shines the most. Take a listen to the castle music from the first Dragon Quest game.

This track draws heavily from the Baroque tradition. It has a simple, contrapuntal style that is similar to Bach and other composers of the era. It uses very classic and straightforward harmonic progressions. When it’s orchestrated though, its classical qualities come through even more prominently. The texture Sugiyama uses here isn’t fully orchestral but rather just a string orchestra, and it gives it an even stronger Baroque character; take a listen here.

This music sets the precedent for the rest of the castle music of the series. They continue to have a lot of influence from the Baroque style and sometimes Classical as well, featuring straightforward harmonic progressions and contrapuntal lines. The style does gradually change slightly though. To see what I mean, take a listen to the castle music from Dragon Quest V:

By this point, Sugiyama has incorporated more “video game music” elements into his style, rather than the almost completely strict Baroque style from before. This track has more dissonances, less counterpoint, and in general is more melodically focused. At this point he also has a more robust soundset at his disposal, so the orchestrations are mostly laid out here. If you listen to the orchestral version from the accompanying Symphonic Suite CD, it is basically the same.

Sugiyama’s battle music also incorporates classical elements in some of the early games of the series. Listen to the battle theme from Dragon Quest II:

This is the orchestral version, which brings out a little bit more of the classical elements. This basic battle track (not the boss fight music in the latter half) has a good deal of Spanish influence, along with a bit of jazz.

The battle music is probably the music that sees one of the biggest shifts away from classical styles. Listen to the battle music rom Dragon Quest VI for another example:

This one really has no obvious classical influences. In fact, the bassline is almost reminiscent of some of Nobuo Uematsu’s battle music from the early Final Fantasy games. The orchestral versions don’t bring out any particular classical influences either, as they do with the previous example. Rather in this case, the orchestra softens some of the rougher edges and gives it an almost cinematic feel which could be mistaken for classical alongside his other works.

Koichi Sugiyama’s town music is a great example of music that sounds less classical when you listen to the original, and then is heavily influenced and changed by orchestration. Listen to the town theme from Dragon Quest IV.

This has some classical influences, but it also has some influences from other video game music. Elements like the hopping bass line and the simple, regular chord progression not structured around V-I is part of what makes it sound less classical then some of the previous examples. It even has a pretty jazzy moment near the end of the loop, with some alternating dissonant chords. But when he orchestrates it, the classical elements really come out:

With this orchestration, the theme sounds more classical. The hopping bassline is masked, and the orchestrations make the harmonies sound richer, closer to an early 20th-century style; listen to Mahler’s 4th symphony if you’d like to hear a comparison. Again, this orchestration became the basis for the new, synth versions for remakes of the game on newer consoles, so seeing how the music progresses across mediums is an interesting insight into Sugiyama’s style.

Town music is also a great opportunity to look at an example of some of his work that is explicitly not classical. I am focusing primarily on the works in the more classical vein, but he also writes music that is in other styles, even in early games. Listen to “Around the World” from Dragon Quest III for instance:

The track is a medley of town music from the game, and it includes a couple of very typical Koichi Sugiyama pieces, like the opening city theme, or the melodic village theme in the middle. But it also features some of his most adventurous music… For instance, listen starting around 01:25. Dragon Quest III features a broad world map with a variety of different towns with different cultures, and he writes music to match. You can hear here his take on Japanese music and Middle Eastern music.

Here are a last handful of examples to show some of his later work. One of the pieces of music that Sugiyama added to the original 8 was flying music, once players started getting the ability to fly in the games. Some of it ranges from lofty and regal (Dragon Quests III and IV), to the more frenetic and goofy style in this track from Dragon Quest VII:

The only classical influences here are in the orchestration and in the use of runs and ornamentations, but otherwise this is a track that draws more on other video game styles. In particular the bouncy accompaniment with the b7 scale degree make this track distinctly less classical.

That’s not to say that he completely abandoned the classical style in later games though. The main field theme of Dragon Quest VIII is a combination of 20th and 21st century classical styles, with lush orchestration.

This track is from the accompanying symphonic suite album for Dragon Quest VIII, and it was actually used in-game in the international release of the game, in place of the original sequenced version used in the Japanese release. The same was done for the Playstation 2 remake of Dragon Quest V. These are examples of just how integral the orchestra is to Koichi Sugiyama’s writing.

Koichi Sugiyama has also written music for a number of other games, not to mention his long history before his entry onto the video game music scene. This is just a brief look at some of his most well known repertoire, to touch on some of the key aspects of his style. He isn’t all about classical pastiche, as a couple of examples showed, but he does draw from those styles very frequently, and makes more use of orchestra than any other video game music composer with whom I am familiar. It is partially thanks to him that video game concert series exist today and continue to grow.

His style is certainly different from some of the other big name composers in the field. Although his impact in the west has been smaller than it has been in Japan, if you are a fan of classical music, role-playing games, or just interested in video game music in general, he is definitely a composer to add to your listening list.

Tags: Analysis, Article, Composers, Dragon Quest, Dragon Quest II, Dragon Quest III, Featured, Game Music, Japanese, Koichi Sugiyama

it seems like only yesterday I Went to Japan and Met Koichi Sugiyama I Was so lucky to meet him and got into his music I Could listen to i like it was so kind of medieval movie I’m hoping his music of Dragon Quest will be as popular as it is today so symphony orchestras can also perform it live to I Can’t wait to get the new dragon Quest 11 symphonic suite album and I Hope to put it on my ipod who Knows Koichi Sugiyama has come along way for doing dragon quest music when it came out and he still is doing it till this day