Featured

-

Chip Music, Demoscene, Featured

The Legacy of KeyGen Music: A Look at Tunes of the Key Cracker Era

January 16, 2019 | Brenna Wilkes | Comments Off on The Legacy of KeyGen Music: A Look at Tunes of the Key Cracker Era Share this

The vast majority of us have been horrible people at some point or another and pirated software or at least emulated games on our computers at least once in our lives. Getting past the morality of it, it’s safe to say we all know the process of downloading an installer alongside a key generator that would help us get to our elicit activities, or an emulator with which to play the ROMs of import games we didn’t get in the states.

If you’re one of those ilk, then you are likely familiar with keygen music, or at least have had an encounter with the niche genre but didn’t pay it much mind. Maybe it was simply an annoyance on the way towards the goal of cracking your ill-gotten software, or maybe it’s a fond memory of the age of Napster, Limewire and pre-torrent times. Having attended MAGFest recently and become more interested in the demoscene, I’ve decided to revisit this.

So what is keygen music?

-

Featured, Game Music, Indie Music

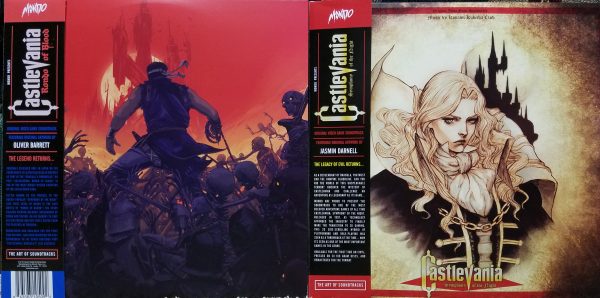

OSVOSTOTY 2018: RYAN’S PICKS

2018 has come to an end and it has been another great year game music. Many folks have written and shared their picks for best video game soundtracks of the year, and now it’s our turn here at OSV. If you missed my picks from last year you can check them out here.

My favorite arrangement album this year arrived early in 2018 and my favorite soundtrack this year may surprise some of you unless you’ve been following me on Twitter.

Read on to see what I picked for my favorite game soundtracks of 2018. -

Featured, Game Music, Indie Music

OSVOSTOTY 2018: BRENNA’S PICKS

Yet another year come and gone and it’s been a year of fantastic VGM. Unfortunately, it’s been another year where I didn’t get to play a whole heck of a lot of games, though what I did had some fantastic music. Now it’s time to do the rundown of my 2019 picks for original soundtrack of the year. While it’s likely disappointing to some, I encourage people to comment with their own list for 2018 OSTs.

-

Featured, Game Music

My Top Five Pieces of Scary Video Game Music (Ryan’s Picks)

As Halloween approaches, over at Original Sound Version we are again looking at scary video game music. Back in 2015 I wrote Game Soundtracks For Your Soul Level 13 where I highlighted some of my most memorable pieces of scary game music. The games I highlighted included the Friday the 13th and Jaws on NES, Silent Hill, Fatal Frame, and Resident Evil 4. This year I’ve written about an additional top five pieces of scary game music. Other writers for OSV will share their selections as we get closer to Halloween.

Read on to see my top five picks for scary game music.

-

Featured, Game Music, Japanese

Matron Maestras – Junko Tamiya (Spotlight)

Capcom has produced and nurtured a variety of female composers over the past few decades. It’s not a huge exaggeration to say that they have been probably one of the most prolific in terms of having so many of their titles featuring women composing the music. The names Manami Matsumae and Yoko Shimomura are well known in the VGM community as legends for their work on the early classic Capcom titles, but there is a score of women who have their names listed as top composer credits in several well-known titles who deserve some spotlight as well for their accomplishments. Junko Tamiya certainly is one of them.

-

Featured, Game Music, Japanese

Matron Maestras – Azusa Chiba (Spotlight)

This article is another entry into the Matron Maestras series, a collection of articles which focus on women composers in the vgm industry.

Today I’ll be talking about Azusa Chiba, one of the composers working for Hitoshi’s Sakimoto’s Basiscape – where her works are scattered across her colleagues – she tends to focus on orchestrating and arranging material for Basiscape. She’s also plays the piano, where she did some piano arrangements for Sakimoto’s work in Valkyria Chronicles and Dragon’s Crown. She has had plenty of time to shine in works like Muramasa: The Demon Blade, and Oh! Samurai Girls. (more…)

-

Anime, Editorial, Featured, Reviews

Wherein we discuss all things Scum’s Wish / Kuzu no Honkai (Review: OSTs and Singles)

Lewd. Tawdry. Filthy. Perverse. Smut.

For decades, those were the words that I associated with virtually all “hentai” Japanese animation and erotic games (eroge). They may have had better plots and production value than a cheesy American porno, but their express purpose was to titillate and turn on. That not only made me uncomfortable, it left me with a moral dilemma time after time; more often than not, I sided with team chaste over time libertine.

(And I won’t even begin to get into concepts like “fan service” or bouncing breasts “chichi yuri.” It’s all quite childish to me. This is not a judgment to any of you who are fans. It’s just where I stand.)

While I very much doubt that this is the first TV anime to break the mold, it is the first one to which I’ve been exposed. Which is to say, I finally found a piece of Japanese pop culture that took on the topics of sex and romantic relationships with some nuance and maturity. I found something I didn’t even know I wanted in Scum’s Wish.

Last year, Fuji TV aired the 12-episode anime adaptation of Mengo Yokoyari’s manga Kuzu no Honkai, which had the unfortunate translated title Scum’s Wish (note: this was not a decision on the part of localization; the title existed from the start in the Japanese manga). Amazon added the English-subtitled localization of the show to their premium channel “Anime Strike,” which is now-defunct, meaning anyone with an Amazon Prime account can now access the show without incurring any additional charge. I would implore you to do so, perhaps before reading the following reviews. We have a lot of ground to cover.

While I will be referencing concepts from the TV show, before continuing on to the music reviews, I cannot state enough how much this anime impacted me. It’s been almost a year, and generally, a week doesn’t go by that I don’t have some memory of the anime or some other reason to recall it. Recently, after (painstakingly) tracking down all the music for Scum’s Wish, I’ve had all the more reason to think on it. But this is not a review of the show itself. I would encourage readers, alongside watching the show, to brush up on the general concept and background of the show by browsing the associated Wikipedia page. The tl;dr — this is a show that is honest about sex, romance, unrequited love, and more. There is no explicit visual content. It is both painfully specific, and surprisingly universal, in scope.

A final note, before the jump: Kuzu no Honkai more accurately translates as follows: “Kuzu” is a term for trash, waste, something used up and discarded. “Honkai” translates to a long-cherished desire, a very deeply-held wish. Something to consider when watching the show, when listening to the OSTs and the singles: who is doing the judging of a human (self or other) as “kuzu” and why? And what are the “honkai”s that rest deep within each character, and within everyday people? Okay, enough existential thought. On to the music! (more…)

| Previous Entries » |

|---|